Research Projects

Principled Inference, Statistics and Graph Neural Networks

As a direct adaptation of the deep neural network machinery to graph data, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs – Hamilton et al. (2017); Kipf & Welling (2016)) have recently gained considerable traction in the machine learning community. Heralded as the breakthrough for machine learning on graphs that would allow the same “AI renaissance” (Battaglia et al. (2018)) that standard neural networks have brought to Computer Vision and Natural Language Processing, GNNs have been suggested as a panacea for a wide number of tasks across disciplines, including molecular design, traffic prediction, and machine learning for knowledge graphs or recommender systems.

.png) Graph Neural Network Block: Illustration of the aggregation (convolution) and transformation steps within each GNN block. GNNs blocks are typically concatenated to allow information to percolate from all parts of the network to each node.

Graph Neural Network Block: Illustration of the aggregation (convolution) and transformation steps within each GNN block. GNNs blocks are typically concatenated to allow information to percolate from all parts of the network to each node.

Of note is their promising application to biological networks (Li et al. (2021)) — a rich and rapidly expanding body of literature, largely due these networks’ versatility in describing systems of various interacting elements.

Yet, despite GNNs’ success on reference datasets in the academic community, both their properties and limitations remain ill-understood. This severely compromises their deployability to any practical or decision-making setting, particularly in a clinical or drug-development context — settings in which the strong requirements for rigour, transparency and reliability clearly highlight the current limitations of Deep Learning methods for graph data.

Motivated by the necessity to shift GNNs from a “black-box” model to an actionable ML method that can be explained, trusted and relied upon in practical settings, we focus on the analysis, improvement and applications of GNNs and graph algorithms at large, and more specifically on the topics of:

- Uncertainty Quantification: UQ methods are a central component in the development of actionable algorithms and methods, as they allow to measure the confidence and/or robustness of the output to uncertainty or noise in the inputs.

- Algorithm Explicability: One of our goals is to study the properties —and consequently the inherent limitations — of current GNN algorithms, particularly with respect torobustness, oversmoothing and performance on various types of networks.

- Interpretablity: We are also interested in studying questions related to the interpretability of GNNs – and providing a clear causal explanation for the outputs.

References

- William L Hamilton, Rex Ying, and Jure Leskovec. Inductive representation learning on large graphs.arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.02216, 2017.

- Thomas N Kipf and Max Welling. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional net-works.arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907, 2016.

- Peter W Battaglia, Jessica B Hamrick, Victor Bapst, Alvaro Sanchez-Gonzalez, Vinicius Zambaldi,Mateusz Malinowski, Andrea Tacchetti, David Raposo, Adam Santoro, Ryan Faulkner, et al.Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks.arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.01261, 2018

- Michelle M Li, Kexin Huang, and Marinka Zitnik. Representation learning for networks in biologyand medicine: Advancements, challenges, and opportunities.arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.04883,2021.

Defining graphs

While networks offer an attractive formalism to study relational data, in many applications, the raw data has to be substantially processed to infer the graph structure before any network analysis can be achieved. In this setting, network inference is thus a crucial and indispensable component of the "graph analysis" pipeline, and on the quality of which depends any downstream analysis. As a result, we are interested in developping algorithms ablet to infer interactions and associations betweem agents in a network, as well as defining confidence levels around the inferred network structure.Applications

COVID-19

With the COVID-19 pandemic, I have participated in a few COVID related projects, including:

- Studying the effect of correlations and deviations from the “iid” hypotheses on the optimality of Group testing. Link.

- Looking at the effect of heterogeneity in the R0 on COVID-19 predictive scenarios. Link.

- Enriching LFA antigen (and antibody) testing with questionnaire data. Link.

- Using questionnaire and local data to assess the transmission risk in live events. Link.

CryoEM Image reconstruction

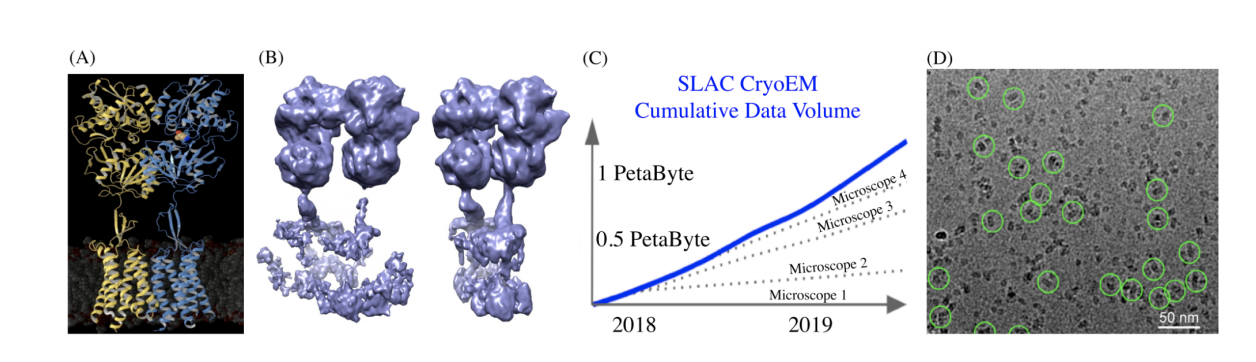

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has revolutionized the field of structural biology by imaging biomolecules in solution. Yet, the vast majority of proteins cannot yet be reconstructred at a satisfying resolution. Such is the case of membrane proteins, a prominent target for over 50% of prescription drugs, including drugs targeting the treatment of neurological disorders and cancers. In this context, the limitation of cryo-EM imaging restricts our understanding of the proteins’ 3D conformations, and consequently, our knowledge of the associated therapeutic mechanisms.

(A) Overall model of the metabotropic GABA-B receptor, a membrane protein that is the target for the treatment of muscle spasms, and alcohol addiction. (B) Principal Component Analysis of raw data, displays poor resolution of the reconstructed shapes between the active and inactive states of the protein (Image courtesy of Prof. Gati). (C) Explosion of cryo-EM data at SLAC National Laboratory (Image courtesy of Dr. Yee-Ting Li). (D) Representative cryo-EM “micrograph” images GABA-B membrane proteins, shown circled in green.

(A) Overall model of the metabotropic GABA-B receptor, a membrane protein that is the target for the treatment of muscle spasms, and alcohol addiction. (B) Principal Component Analysis of raw data, displays poor resolution of the reconstructed shapes between the active and inactive states of the protein (Image courtesy of Prof. Gati). (C) Explosion of cryo-EM data at SLAC National Laboratory (Image courtesy of Dr. Yee-Ting Li). (D) Representative cryo-EM “micrograph” images GABA-B membrane proteins, shown circled in green.

As part of a collaboration led by Prof. Nina Miolane (UC Santa Barbara) and Prof. Cornelius Gati (USC), and together with Dr. Frederic Poitevin (SLAC) and Prof. Khanh Dao Duc (UCB), we are working the development novel mathematical and statistical tools that enhances the resolution of cryo-EM reconstructions, particularly targeting membrane proteins. More specifically, we aim to enrich methods for unsupervised deep learning, such as (variational) autoencoders and/or generative adversarial networks, with constraints on the geometry of shape spaces. The objective of this approach is to allow accurate and robust disentanglement of shape, motion and imaging parameters.

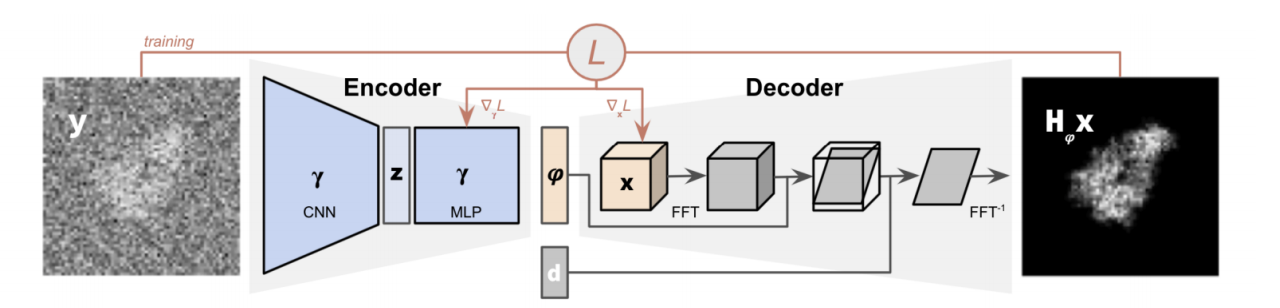

The input cryoEM image y is encoded into a pose phi by the encoder. The decoder outputs the tomographic projection of the biomolecular structure oriented at phi, and then corrupted by the microscope’s contrast transfer function (CTF).

The input cryoEM image y is encoded into a pose phi by the encoder. The decoder outputs the tomographic projection of the biomolecular structure oriented at phi, and then corrupted by the microscope’s contrast transfer function (CTF).